Addressing Disproportionate Impacts of Climate Change through Local Community-based Interventions

November 1, 2024

Muhammad Aatir Khan, IIE New Leader

In a country that lies in the top ten most vulnerable to climate change, Pakistan holds a citizenry key to mitigating the effects of severe weather disasters. As an education policy expert, Dr. Aatir Khan has seen first-hand the damage these disasters have on educational infrastructure. In addition to his work as a professor, Khan has created programs for lower and higher secondary school students to first learn more about climate change and its effects, and then take concrete actions to mitigate the effects of climate change. In his second blog entry, Dr. Khan argues that significant investment in education is one of the most important tools to adapt to and solve for climate change in vulnerable communities.

As a developing country with protracted political and socioeconomic challenges, Pakistan is especially vulnerable to the impacts of climate change; often, it only worsens the situation. About a quarter of the country’s GDP comes from the agriculture sector which is severely impacted by climate change and more disproportionately among small farmers and hired laborers than large agriculturalists. Low-income communities don’t have the infrastructure or resources to withstand extreme weather events or get adequate health care to address the issues. Their level of awareness of climate change and financial resources are also limited, which prevents them from taking coordinated preventative measures.

In addition, there is a dearth of state-provided resources for these communities. The infrastructure for public schools already needs a lot of improvements. In a lot of cases, especially in the major cities, there is a lack of proper maintenance and climate-proofing. In others, the buildings are already very damaged or even non-existent in some cases. Education is already seen as a luxury, and the perceived lack of tangible outputs from an ailing system further contributes to student dropout rates because many low-income students work to support their families. Parents are even more hesitant to send female students to damaged schools, or to schools that don’t have functioning toilets.

Physically laborious jobs compounded by climate-related heatwaves and pollution worsen the impacts on low-income communities. Economic disparities also prevent them from taking preventative measures, seeking quality healthcare, or otherwise coping with climate-related health issues. Communities that rely on agriculture or other climate-sensitive sectors, such as fishing or informal labor markets, are evermore vulnerable to climate change.

Here, public policies are largely made by the political elite with little to no input from the impacted communities. This results in broad-stroke solutions that fail to capture the nuances of the issues and, thereby, are rendered ineffective or worse. For example, investing in large developmental projects such as dams or renewable energy is common. While both are important, there is a dire need for inclusive cost-benefit analyses. These mega projects mostly benefit the already privileged and often displace or disrupt the low-income communities that are already struggling. Further, they take too long to complete—if they are ever completed—they almost always exceed their budgets, and lack the proper maintenance and upkeep required for long-term utility. Hence, it is critical to engage the communities and have equitable representation to ensure a diverse perspective and effective needs analysis before any project is undertaken. Moreover, there is it is imperative to directly invest in low-income and marginalized communities, including providing them with education and training to enhance their skills and allow them to cope with climate impacts.

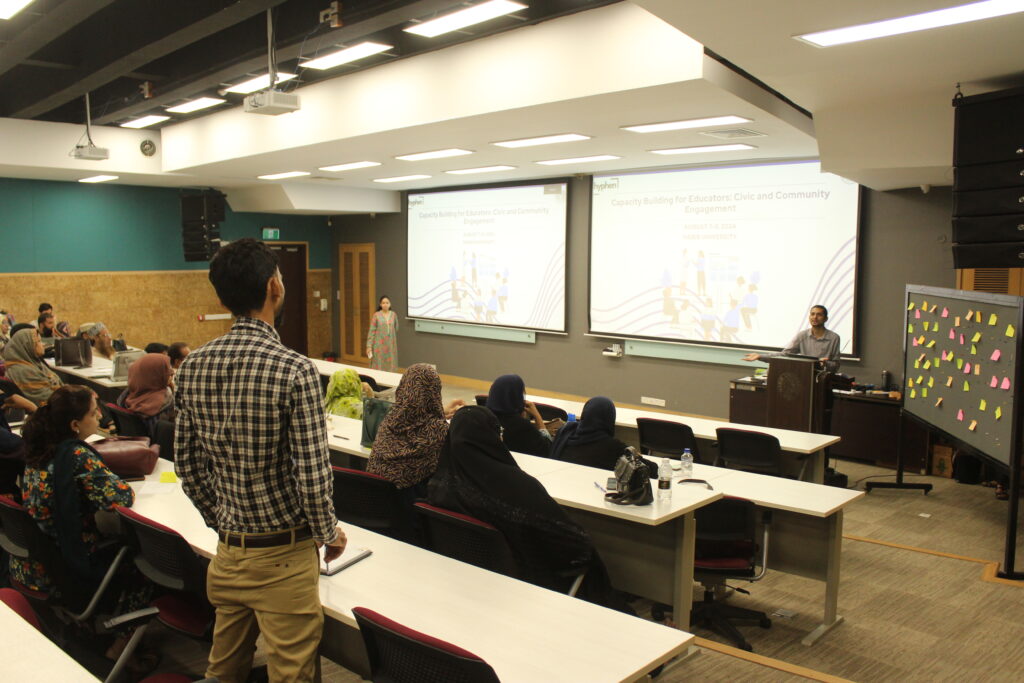

The civic club project that I am piloting aims to do just that. By working with public schools, I am seeking to engage local communities and involve them in the climate change discourse. The goal is to raise awareness so people can understand the broader context of climate change, which will help them better understand their own lived realities and develop solutions that work for them. We are working directly with marginalized communities to provide them with the tools to act. The project does not give them financial resources but rather focuses on capacity building for the youth so they can work with their communities and take action on their own to address their local issues. This is done in two steps: first, through a capacity-building workshop for school heads and club advisors of participating schools; and second, through an onboarding training for the student club leaders to better equip them with the tools to manage the clubs.

Finally, my project aims to increase civic participation among Pakistani youth, where political apathy and a general lack of trust and faith in the government have taken root for generations. The goal is to engage with local government representatives so that they can be better informed of their rights to hold the government accountable. At the same time, it also emphasizes the need for collective action to address local issues to discourage complete reliance on government actors.

Education is a very powerful tool. It is not possible to address systemic social issues in a short span of time, but by educating the youth and giving them the requisite tools, we can hope to see positive generational shifts in society.

Named in honor of IIE’s Centennial and association with the Fulbright Program, the IIE Centennial Fellowship seeks to help enhance Fulbright as a life-long experience and recognize alumni whose work embodies the program’s underlining values of mutual understanding, leadership, global problem solving, and global impact.