Kyle Rausch, EdD, Director of Education Abroad,

Office of Global Engagement, Purdue University Northwest

Over the past several decades the landscape of education abroad has seen a shift. Although junior year abroad and lengthier semester exchange programs were once the norm, short-term, faculty-directed programs have quickly dominated the scene. IIE’s most recent Open Doors report indicates that of U.S. students who study abroad, 65% of them do so on a short-term program (summer or eight weeks or less).

The reasons for this are plentiful:

- The face of U.S. higher education continues to diversify. Students who are underrepresented in education abroad are less likely to pursue longer-term programs due to concerns about cost, perceptions of missed opportunities, or a potential negative effect on time to graduate.

- Degree plans have become more rigid. As institutions look to increase their 4-year graduation rates, degree plans have become more lock step making it difficult for students to fit in a longer study abroad program. This is especially true for more ‘hard skill’ based majors such as STEM majors. Coincidentally, these majors are now the most popular.

- Students are busier than ever and inundated with opportunities. With the cost of higher education increasing and more students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds pursuing a higher education, students are having to hold jobs while keeping pace with their studies. Couple this with the fact that they feel pressured to be involved in co-curricular activities such as internships to remain competitive post-graduation in the job market, education abroad has a lot with which to compete.

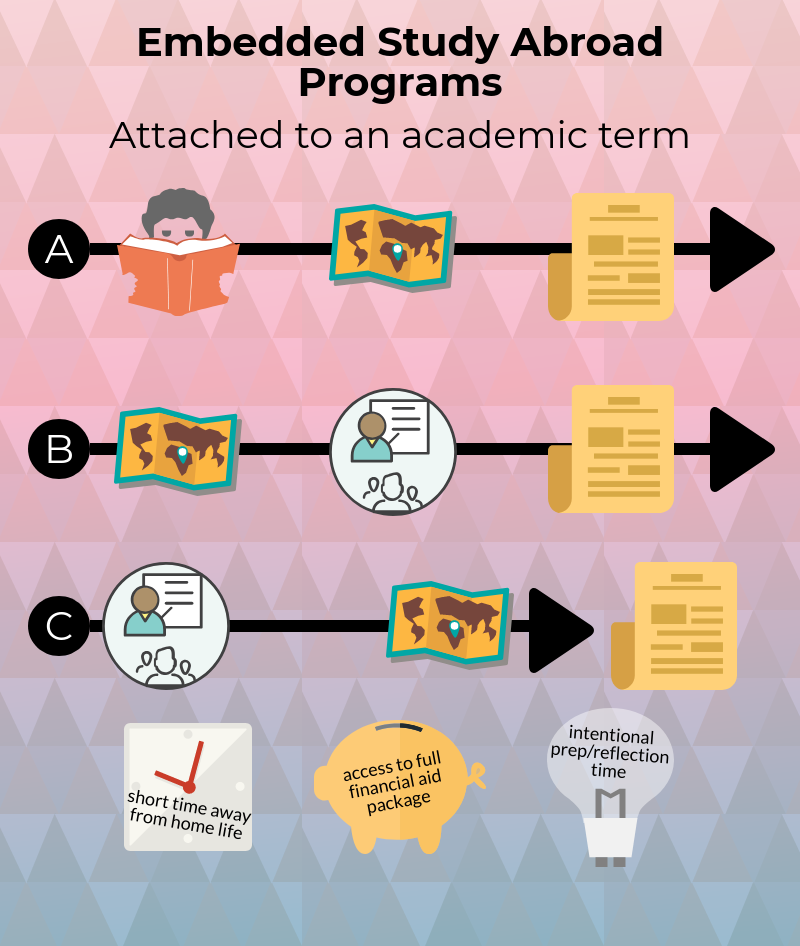

Given this context, it is no surprise then that students are opting for short-term programs. Although short-term, faculty-directed programs have historically been criticized as being less-than ideal for cultural competency gains and branded as “island” programs, there are models of programming that are helping to increase access to education abroad for underrepresented students, while improving the potential for intercultural learning to occur. More and more institutions are turning to embedded program models in order to meet these needs. Embedded programs are short-term programs that are attached to or embedded in a semester course.The infographic below illustrates three possible examples:

Model A: A spring semester course where the travel component happens during spring break. Students meet and learn about the course subject and destination to where they will be traveling, go abroad for 7-10 days over the break, and then return to process and submit course deliverables.

Model B: At some institutions, there is the possibility to attach the abroad component of a course immediately prior to the semester. Students go abroad and then return to campus to take a formal course to unpack what they observed.

Model C: Attach the abroad component to the end of the semester before the following term begins. In this example, students have the entirety of a course to prep for the international trip. Often times grades of “incomplete” may be assigned until final projects and other deliverables are due upon the students’ return.

Why are these models a good fit? Because they allow for the possibility of deeper intercultural learning on a short-term program and can improve access for underrepresented students. A long-standing criticism of short-term faculty-directed programs that run during the summer is that students only walk away with a superficial understanding of the host culture. Pre-departure orientations are often 1-2-hour sessions that cram in a ton of information, more related to health & safety than cultural adaptation or key aspects of the host culture’s history, politics, language, and other aspects. Embedded study abroad programs allow for more time to be spent to situate the topic being studied within the host culture, cultural adaptation to be introduced, and for structured reflection to occur.

In terms of increasing access to underrepresented students, these programs can potentially meet the needs of diverse groups of students.

First, consider funding. At many institutions, federal financial aid is much more limited during the summer. By embedding a study abroad program within a fall or spring semester, students often have access to their full financial aid packages to help defray the costs of studying abroad. Furthermore, the shorter duration of these programs usually means that program fees are lower.

Embedded programs are not only a model for students from low socio-economic backgrounds, though. Many institutions are seeing increased enrollments from non-traditional students, military veterans, and first-generation college students. Increasingly, campuses are also operating online degree programs for students around the globe. Shorter programs may be the only option for providing these students with study abroad experiences. Consider the case whereby a single parent decides to go back to school to complete their degree as part of a university’s online program. Working full-time means getting time off and leaving their family for 3+ weeks would be near impossible. However, a spring break program not only means that they able to participate in a study abroad experience, but also engage in real-time with other students and faculty from their university. It can be a powerful learning opportunity for these students who may otherwise never have the chance to experience a traditional collegiate setting.

At my previous institution, we piloted four programs and in just four short years this model grew to us sending close to 30 embedded programs out. The neat byproduct of these programs in reaching online students was not something we had necessarily planned for. Given the high percentages of these and other underrepresented students the institution serves, it was clear we had found an important model for education abroad that helped meet our students’ needs.

It is important to have a diverse portfolio of programs that address the needs of all of your students. Most institutions are now serving a hugely diverse array of students and so our education abroad portfolios should reflect their diverse needs. If your institution is looking to increase access for students traditionally underrepresented in education abroad, consider how you might be able to leverage embedded faculty-directed programs as a way to overcome this obstacle while bolstering the intercultural learning that can occur on faculty-directed programs.

Purdue University Northwest is an IIE Generation Study Abroad Commitment Partner. Representing an alliance of over 800 U.S. and international colleges and universities, educational associations and organizations, and country partners, these Commitment Partners have pledged strategic actions in support of the Generation Study Abroad initiative’s goal to promote equity and increase access for U.S. student participation in study abroad since 2014.